Spatial Intelligence is Natural

AI needs world models, and the world is spatial

Professor Fei-Fei Li, one of the key figures in the development of modern AI, is among the latest luminaries to advocate for a rethinking of our approach to creating artificial intelligence and autonomy.

Alongside others such as Yann LeCun she advocates the development of world models, and previews the work of her own lab at Stanford, and her startup World Labs.

Fei-Fei uses the term ‘spatial intelligence’ to describe the missing piece of the puzzle for AI, and refers to the tremendous abilities of animals to navigate space as a motivating factor. At Opteran we’ve been on this page for the last 5 years in developing what we call ‘natural intelligence’, and built our approach on an even longer legacy of research into how animal brains represent and process space, including our own fundamental research. In the following, I’ll explain how this is already leading to cutting-edge products for robot autonomy, and how we believe it represents the future for full-featured artificial autonomy.

To understand space, understand the brain

Modern AI is based on statistical machine learning, which extracts associations from within datasets, and turns these into decisions about what to do, and predictions about what should happen next. Starting in the 2010s, with the availability of internet scale datasets as well as curated datasets such as Professor Li’s ImageNet database, and with data centres for running training algorithms, the current approach to AI took off. Using training algorithms running on general, blank-slate, neural networks, rapid advances were made first in image recognition, then other modalities like speech and video, in turn leading on to recent generative AI technologies such as GPTs.

It has long been recognized, however, that statistical approaches to AI are hugely data and training intensive. Where the internet provides a good source of data, such as for text, images, video, and audio, this can be scraped. But there are already concerns that generative AI is running out of data in these domains, and statistical approaches struggle with truly novel scenarios that fall outside of the training data distribution. Further, for the application of these technologies to robotics and autonomous systems, data collection is tremendously challenging leading to the increased use of solutions such as simulation, which come with their own problems.

Professor Li’s diagnosis is correct, that statistical approaches are lacking exactly because of their statistical nature, and that simply scaling up the training data will not help with this problem. We fully agree with her that world models, grounded in spatial intelligence, are needed for AI to progress. Where we differ is in the approach for robotics. Like LeCun, Li proposes the development of explicit world models. Also like LeCun, she envisions these as using novel algorithms but fundamentally remaining based on a training paradigm, consuming data to learn how the world works.

At Opteran, and in the research in my lab that led to its formation, we’ve taken a different view from day one. Rather than follow the dominant, data-driven, paradigm, I advocated learning lessons from the brains of animals, especially small-brained ones such as insects. Real brains contain so much more variety in structure and function than modern statistical AI does, yet represent an almost completely untapped resource in terms of discovering algorithms for autonomy. And while 15 years ago data on how brains are put together were lacking, modern neuroscience is leading to an avalanche of understanding.

At Opteran we use insights generated from understanding true brain function to build our own spatial intelligence ‘foundation models’. Unlike modern AI these are not based on training, but on reverse-engineering the algorithms that evolution has fine-tuned over hundreds of millions of years, starting with how brains perceive the world and represent space within it.

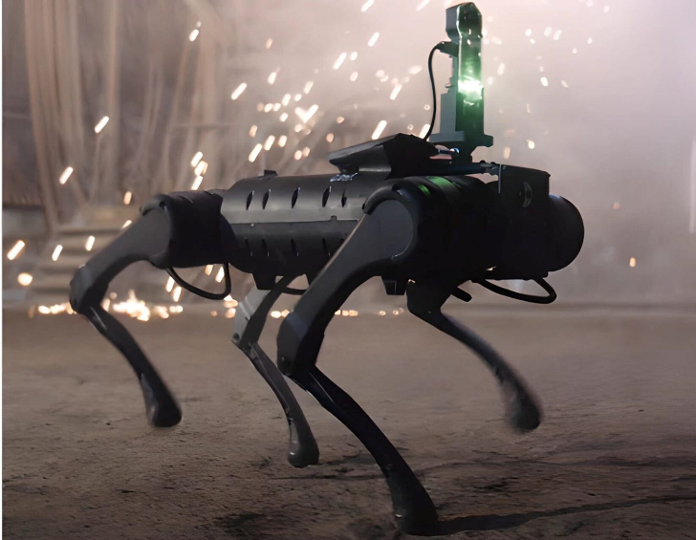

How this approach yields technical and commercial advantage is already being demonstrated. As my co-founder Alex Cope just wrote, we have now disrupted the incumbent approach to robot navigation, visual simultaneous localization and mapping (VSLAM), simultaneously improving reliability while decreasing memory and compute requirements, and total deployment costs, typically by several orders of magnitude.

Spatial intelligence is the foundation for physical AI

We believe that disrupting navigation is only the beginning of the Opteran journey, albeit a very valuable one. Once efficient and reliable understanding of space is solved, we are well placed to interface with other technologies such as generative AI and leverage their capabilities to produce more and more capable autonomous systems. Just as brains evolved to solve movement first, then added more and more complexity on top of those foundations, such as the cortex that inspires modern AI methods, by building spatial intelligence we will unlock a route to robust and adaptable physical AI.

Looking forwards

Like Fei-Fei Li, we agree that spatial intelligence is the foundation of the truly generalizable intelligence that our technology and society will need as we deal with an aging and declining population, resource constraints, and other challenges. I couldn’t be more excited to see what disruptors of the current paradigm, such as Opteran, and World Labs, are going to achieve next.

James Marshall,

Founder Science Officer, Opteran